Image Credit: Sonse via Wikimedia Commons

In November 2012, Irish Times Social Affairs Correspondent Kitty Holland broke the story about the death of Savita Halappanavar at Galway University Hospital.

Six and a half years later, Ireland wakes up a different country with 66.4% voting to repeal the Eighth Amendment.

In many ways, Holland’s reporting of Savita’s story was the starting point for yesterday’s historic result in Ireland. The story gripped the nation, inspiring nationwide protests and, eventually, a review of Irish abortion laws.

For journalists, Savita’s story and Holland’s reporting of it is a reminder that great stories have great consequences.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the rest of the island. Six and a half years later, Northern Ireland wakes up the same, if not arguably worse.

Northern Ireland: out of step with the UK – and now Ireland

The 1967 Abortion Act applies to everywhere in the UK except Northern Ireland.

In NI, two pieces of outdated legislation – the 1865 Offences Against the Person Act and the 1925 Criminal Justice Act – decree that abortion can only be carried out if there is a risk to the mother’s life or threat to her mental and physical health that is likely to be long-term or enduring.

These two pieces of legislation are not only out dated due to physical age, but are also increasingly out of step with a progressively liberal Northern Ireland.

In 2004, the Family Planning Association brought the NI Department of Health to court, arguing that access to abortion services in NI is a “postcode lottery”. The Department of Health responded by publishing guidance for health and social care professionals in 2016.

In February 2018, the United Nations’ expert committee concluded that the UK “violates the rights of women in Northern Ireland by unduly restricting their access to abortion”.

The list goes on – and so does the social injustice.

Traditionally, abortion legislation has been a “conscience issue”, allowing the DUP to block any reform through the petition of concern.

The cross-community petitions have been used more than 100 times. In November 2015, the introduction of same sex marriage was vetoed by the DUP.

However, the DUP no longer has the number of MLAs to enforce such a petition, raising hopes that one day Northern Irish society can catch up with the rest of the UK and Ireland.

Other political parties in NI have a confused position on abortion; some indicating that they are pro-choice, others that they are pro-life but regard views on termination of pregnancy as a matter of conscience for members.

Meanwhile, none of these views are of any consequence given the current political deficit.

Health may be a devolved matter, but what happens when there is no devolved government?

Not much going by the past 14 months. With no NI Assembly in place since its collapse in January 2017, Northern Irish politics – and society – is at a standstill.

Indeed, yesterday’s abortion referendum in the Republic of Ireland ironically took place exactly 14 months to the day since the breakdown of the NI Assembly and Executive on 26 January 2017.

Herein lies the wider problem Northern Ireland is currently facing. Much like the NI Assembly, women in Northern Ireland currently have no voice – and no choice.

And, yet again, the lack of an NI Assembly has been wholly treated as an NI problem by the majority of UK media. Until now.

Theresa May have a problem

Yesterday’s landslide result in the Republic of Ireland means Northern Ireland is yet again set to be Prime Minister Theresa May’s biggest problem – in addition, of course, to the small matter of the Irish border post-Brexit.

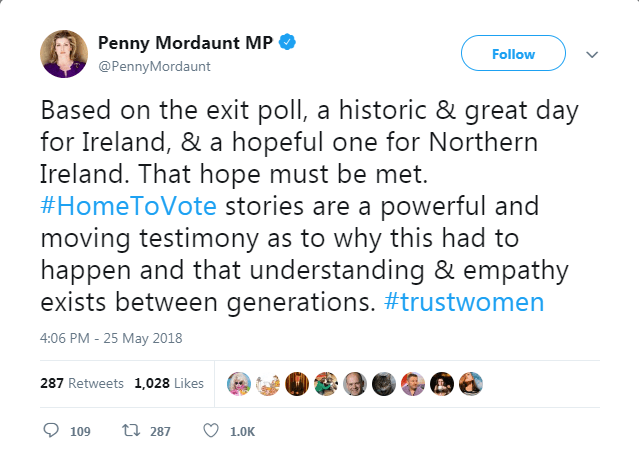

Minister for Women and Equalities Penny Mordaunt has been publicly piling the pressure on the British PM since Friday: “Based on the exit poll, a historic & great day for Ireland, & a hopeful one for Northern Ireland. That hope must be met.”

Mrs May, a former Women and Equalities Minister herself, even tweeted her congratulations: “The Irish Referendum yesterday was an impressive show of democracy which delivered a clear and unambiguous result.”

But well wishes are one thing, and political will and change another.

Let’s not forget that Mrs May’s majority in the House of Commons relies solely on a confidence-and-supply deal with the DUP.

And the DUP has proved it isn’t afraid to use this to its advantage, as seen when DUP leader Arlene Foster single-handedly put a stop to the December Brexit agreement with a simple phone call.

There is plenty to celebrate after yesterday’s referendum in Ireland. The once socially conservative Republic has yet again proved itself more liberal than part of the UK – with a two-thirds majority and the highest turnout of any referendum in the country since 1992.

But Northern Ireland is a different country in more ways than one.

With no NI Assembly and a British government propped up by the highly conservative DUP, it seems neither the politicians nor the women of Northern Ireland will be given neither a voice nor a choice anytime soon.